Gwendolyn Bennett

A versatile artist and writer, Gwendolyn Bennett (1902-1981) was a rising star of the New Negro movement in the 1920s. Her vivacious personality made her a favorite at literary salons and parties, and her talent and training, combined with pluck, determination, and encouragement from her parents and other Black artists and intellectuals of the Harlem Renaissance, helped her succeed in the face of many obstacles.

She studied fine arts at Columbia University and became the first Black graduate of the Pratt Institute. At only 22, she was hired by Howard University to teach in their newly formed fine arts department. The next year, she won a sorority scholarship to study art in Paris, where she mingled with Ernest Hemingway, Henri Matisse, Paul Robeson, Gertrude Stein, and other modernist celebrities. Her art, poetry, and other writings appeared in the most important race magazines of the day, The Messenger, Opportunity, and Crisis, and in the influential anthologies, Countée Cullen’s Caroling Dusk (1927), Charles S. Johnson’s Ebony and Topaz (1927), and James Weldon Johnson’s The Book of American Negro Poetry (1931). She co-edited and contributed to the celebrated Black arts magazine Fire!! (1926), wrote a monthly arts column for Opportunity called “The Ebony Flute” (1926-1928), and served as editor for Black Opals (1927).

Although Bennett continued to write poetry and work in arts education and advocacy, she began to fade from the spotlight in the 1930’s, her creativity hindered by personal and political crises: financial struggles, marital troubles, harassment from both the KKK and FBI, and other intersectional obstacles. Despite efforts by scholars such as Sandra Govan, Maureen Honey, Nina Miller, and Belinda Wheeler to restore her legacy, including the 2018 publication of her Selected Writings, Bennett remains an understudied figure in the Harlem Renaissance.1The most significant studies of Bennett to date are Sandra Y. Govan’s 1980 dissertation, Gwendolyn Bennett: Portrait of an Artist Lost, which restored Bennett from near oblivion, and Belinda Wheeler and Louis J. Parascandola’s Heroine of the Harlem Renaissance and beyond: Gwendolyn Bennett’s Selected Writings (The Pennsylvania State University Press, 2018), whose expert editing have made much of Bennett’s work available in a single volume for the first time. Nina Miller and Maureen Honey devote chapters to Bennett, and T. Denean Sharpley-Whiting details her Paris residency. See Miller, Making Love Modern the Intimate Public Worlds of New York’s Literary Women (Oxford University Press, 1999); Honey, Aphrodite’s Daughters: Three Modernist Poets of the Harlem Renaissance (Rutgers University Press, 2016); Sharpley-Whiting, Bricktop’s Paris: African American Women in Paris between the Two World Wars (State University of New York Press, 2015).

Education

The road to becoming an artist was a long and rocky one for Bennett, characterized by peaks of achievement and valleys of doubt and discouragement. Born in 1902 in Giddings, Texas, to doting, well-educated, Black professionals (her mother was a teacher and her father a lawyer), she enjoyed the benefits of a middle-class upbringing, including higher education and access to art, music, and theater.

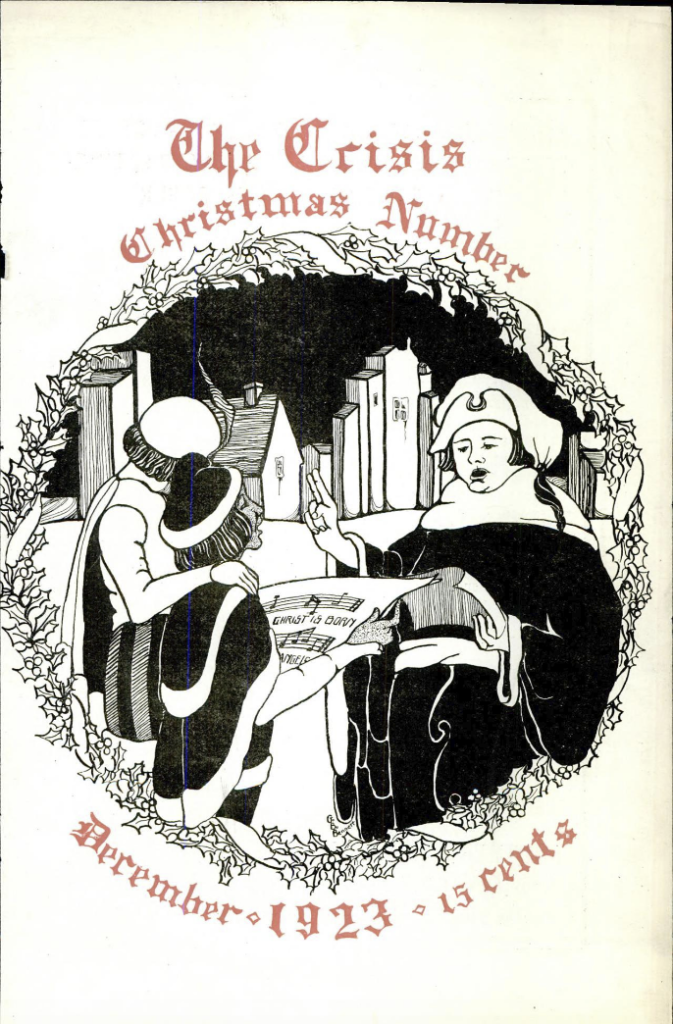

After completing high school in Brooklyn, she studied Fine Arts at Columbia University, where she befriended Langston Hughes. Put off by racism at Columbia, she completed her degree at the Pratt Institute, where she was the first African American to receive a degree. In 1923 at age 21, she published her first poem in Opportunity and a cover illustration for the Crisis:

The Crisis Christmas Number cover drawing depicts an interracial group of carolers dressed in old English apparel. The village setting juxtaposes a country cottage with slender buildings that evoke stylized skyscrapers. This interest in interracial relations and blending of ancient and modern elements are characteristic of her early work.

Early Achievements

In 1924, Bennett was invited to join the faculty of the newly formed fine arts department at Howard University, the preeminent HBCU. She had one-woman exhibitions of her original batik designs, received a scholarship to study art in Paris in 1925, and, two years later won a prestigious fellowship to study art at the Barnes Foundation. She co-edited the celebrated avant-garde magazine Fire!! (1926) and contributed her critically acclaimed short story “Wedding Day.” The same year, she became an assistant editor at Opportunity, publishing a monthly arts column called “The Ebony Flute” that documented the achievements and movements of Black artists (1926-28). As a poet, artist, editor, and educator, Bennett seemed to have it all, as Maureen Honey puts it: “By 1928, Gwendolyn Bennett was a star, the epitome of a New Negro artist blazing trails forward into the twentieth century of modern America with her creative writing, visual art, youth, beauty, and education” (Aphrodites’ Daughters 99).

Bennett’s early achievements were celebrated in the Black presses, albeit in ways that expose the challenges facing a young, aspiring Black woman at the time. In an article announcing her appointment at Howard University, The Pittsburgh Courier, one of the preeminent African American newspapers, featured the headline, “Easy to look at, easy to study from.” The headline draws attention to her good looks rather than her professional accomplishments, insinuating the sexual availability stereotypically associated with Black women at the time.

Trauma & Loss

Even as she persevered in the face of public scrutiny, Bennett private faced trauma and obstacles. Her parents divorced when she was five years old, and her father, dissatisfied with the custody arrangement, kidnapped her at the age of eight, moving with her to various cities on the East coast to avoid detection. She did not reconnect with her mother until 1926, an uncomfortable reunion that deepened their estrangement.

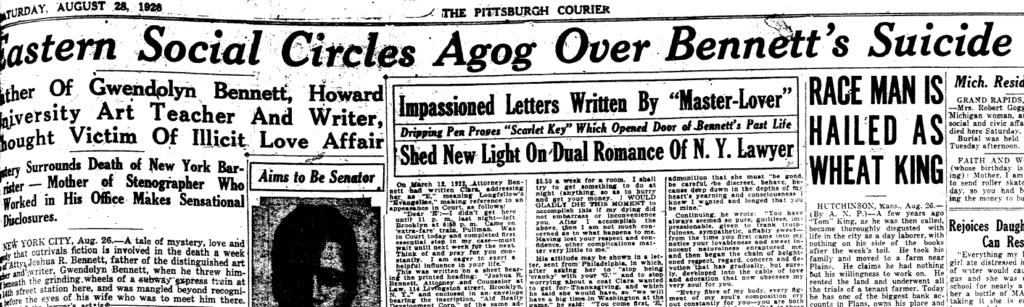

Despite her talent as an artist and writer, Bennett struggled to fulfill her potential as an artist. Lonely, homesick, and poor in Paris, she struggled to find a studio and create art. Soon after her return to the U.S., her father was killed in a subway accident—a scandal one reporter described as “a tale of mystery, love and tragedy that outrivals fiction.” His highly publicized death was alleged to be a suicide brought on by the exposure of his affair with his former stenographer, and the reporter who detailed the lurid drama identified him as “father of the distinguished art teacher and writer Gwendolyn Bennett.”

Bennett faced another setback when she became engaged to a medical student at Howard University and was compelled to resign her position because fraternizing with students was prohibited. She faced a brief period of unemployment, disguising herself as a Javanese woman to gain employment in a New York batik studio and then taking a job teaching school in Maryland.

Bennett had to give up her beloved “Ebony Flute” column to move with her new husband to Florida for his medical practice. There, they were terrorized by the K.K.K. and plagued by a fruit blight that devastated the local economy. Cut off from the Harlem artistic community that sustained her and at odds with her husband, Bennett again found it difficult to write or paint. When his medical practice failed, they moved to Long Island in 1932. Their marriage was further strained by his alcoholism, infidelity, and unemployment. When her husband became too sick to work, Bennett had to pose as a single woman in order to get a job to support them and pay their mortgage.

Later career

After her husband died in the mid-thirties, Bennett returned to Harlem, but the thriving arts community had been wracked by the Depression and further fragmented by relentless harassment from the FBI, whose decades-long investigations of Black writers for supposed Communist affiliations sowed fear and distrust, making it too risky for Bennett to publish poetry. Bennett turned her creative energies to a series of demanding, low-paid, and short-lived teaching and arts advocacy jobs, one of which she lost due to allegations of Communist activities. Longing for stability and a happy marriage, she turned away from the art world, married white educator and writer Richard Crosscup in 1940, worked for the Consumers Union from 1948 to 1968, and in 1970 moved with Crosscup to Pennsylvania to run a successful antiques shop.

References

The most significant book-length studies of Bennett to date are:

- Sandra Y. Govan’s dissertation, Gwendolyn Bennett: Portrait of an Artist Lost (ProQuest Dissertations Publishing, 1980), which restored Bennett from near oblivion.

- Belinda Wheeler and Louis J. Parascandola’s Heroine of the Harlem Renaissance and beyond: Gwendolyn Bennett’s Selected Writings (The Pennsylvania State University Press, 2018), which makes much of Bennett’s work available in a single volume for the first time.

See also chapters and sections on Bennett in:

- Nina Miller, Making Love Modern the Intimate Public Worlds of New York’s Literary Women (Oxford University Press, 1999).

- T. Denean Sharpley-Whiting, Bricktop’s Paris: African American Women in Paris between the Two World Wars (State University of New York Press, 2015).

- Maureen Honey, Aphrodite’s Daughters: Three Modernist Poets of the Harlem Renaissance (Rutgers University Press, 2016).