A Studio of One’s Own

What would an African American woman need to be an artist in the 1920s, if, according to Virginal Woolf, a white English woman of the same era needed a room of her own and £500 a year?

Inspired by Saidiya Hartman’s Wayward Lives, Beautiful Experiments, this scene attempts to convey the sensory landscape and psychological reactions of a young Black woman trying to make her way as an artist in Paris, New York, Washington D.C., and Florida in the 1920s. Hartman employs “a mode of close narration, a style which places the voice of narrator and character in inseparable relation, so that the vision, language, and rhythms of the wayward shape and arrange the text.”1Hartman, Saidiya. Wayward Lives, Beautiful Experiments: Intimate Histories of Social Upheaval. W. W. Norton & Co., 2019. pp. xiii-xiv) In a similar vein, I collate excerpts from Gwendolyn Bennett’s published and archival writings to create a coherent story out of a complicated, multi-faceted life. To highlight the artifice of my intervention in her story, I narrate in the present tense—a gesture to the present condition of writing (and reading). To blend her first-person accounts into the narrative, I reset them in the third-person, punctuating the narrative with block quotations that maintain the integrity of her voice, perspective, and style. Italicized phrases are adapted from Bennett’s diaries, letters, autobiographical essays, and interviews.

January 1925

Gwendolyn Bennett, Howard University’s newly hired art instructor, wins a $1000 Delta Sigma Theta scholarship to study in Paris for a year. The campus is agog with the news of her award. Everybody is congratulating her and wishing her all sorts of luck.2Gwendolyn Bennett, letter to “Mumsey and Daddy” [Joshua and Marechal Bennett], Monday, January 5, 1925. Gwendolyn Bennett Papers. Yale Collection of American Literature, Beinecke Rare Book and Manuscript Library. https://collections.library.yale.edu/catalog/16817908 The Black press trumpets her achievements, casting the 23-year-old prodigy as a rising star of the New Negro renaissance. Noting that “Few Negroes have had or have [her] wonderful (marvellously so) opportunities,” her father predicts that she will join the ranks of Michelangelo, James Whistler, and Henry Tanner.3Joshua Bennett, letter to “Our Dear Baby” (Gwendolyn Bennett), Monday, January 12, 1925, pp. 4-5. Gwendolyn Bennett Papers. Yale Collection of American Literature, Beinecke Rare Book and Manuscript Library. https://collections.library.yale.edu/catalog/16817908 She already feels famous, so she assumes W.E.B. Du Bois has heard the good news when she writes to him asking, May I presume upon your friendship and ask for any advice you might have to offer me about my going abroad:4Gwendolyn Bennett, to W. E. B. Du Bois, January 19, 1925. W. E. B. Du Bois Papers (MS 312). Special Collections and University Archives, University of Massachusetts Amherst Libraries. https://credo.library.umass.edu/view/full/mums312-b027-i385

Even Dr. Du Bois’s clipped, patronizing reply isn’t enough to dampen her spirits:

With or without his advice, she is still walking on air.5Gwendolyn Bennett, to W. E. B. Du Bois, January 19, 1925. W. E. B. Du Bois Papers (MS 312). Special Collections and University Archives, University of Massachusetts Amherst Libraries. https://credo.library.umass.edu/view/full/mums312-b027-i385

Thursday, June 24, 1925

But when she arrives in Paris, her high hopes are dashed by disappointments:

This was my first real day in Paris. Early in the morning I betook me a taxi to the Latin Quarter. The first place I turned was to the Foyer international des étudiantes. I found out that the student residence would soon close for vacation and that even a room for the summer could not be had before July 15th. That was bad enough but they told me further that they did not take art students as residents for the school year…because it was their policy to cater to the “more serious minded student.”6Paris Diary, Thursday, June 25, 1925. Bennett, Gwendolyn. Gwendolyn Bennett Papers, 1916-1981. Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture, The New York Public Library.

She makes her way to the Dome to meet Ann Case for lunch, but her friend is nowhere to be found in the crowded café. She wanders about the Quartier alone. She stops at the Hotel Jeanne D’Arc to call on the artist she hopes will be her comrade-in-arms in Paris, only to learn that Miss Laura Wheeler has moved to Neuilly. On to Madame Mellon’s Pension. She can’t take her into her home until July 3. Then with Madame Mellon through the streets until they finally get a room for her at the Hotel Orfila, 60 Rue D’Assas, 18 francs per day including “petite dejeuner.”7Paris Diary, Thursday, June 25, 1925. Bennett, Gwendolyn. Gwendolyn Bennett Papers, 1916-1981. Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture, The New York Public Library.

The room is cramped and dark, but it’ll do—at least to sleep in. There’s no space for art making or even art supplies, but she doesn’t have any yet. A homesickness more poignant and aching than anything she can ever imagine holds her in its grip.8Paris Diary, Sunday July 26, 1925. Bennett, Gwendolyn. Gwendolyn Bennett Papers, 1916-1981. Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture, The New York Public Library. Reprinted in Bennett, Gwendolyn. Heroine of the Harlem Renaissance and beyond: Gwendolyn Bennett’s Selected Writings. Eds. Belinda Wheeler and Louis J. Parascandola. The Pennsylvania State University Press, 2018. p. 180.

She asks the proprietor to call her friend Aulston Burleigh and gets the shock of her life when they send him right up to her bedroom. He assures her that that was quite their way of doing things. She isn’t comfortable at all so they go out. He takes her to dinner and then for a long taxi ride all over the city.9Paris Diary, Thursday, June 25, 1925. Bennett, Gwendolyn. Gwendolyn Bennett Papers, 1916-1981. Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture, The New York Public Library.

Safe and secure in the taxi, she relaxes for the moment.

Paris is a marvelous place…10Paris Diary, Thursday, June 25, 1925. Bennett, Gwendolyn. Gwendolyn Bennett Papers, 1916-1981. Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture, The New York Public Library.

Friday, June 26, 1925

But the next day is no better:

Could I mark this day I should put a black ring around it as one of the saddest days I have ever spent. For two days now it has rained—the people tell me that this is typical Paris weather. A cold rain that eats into very marrow of the bone. No umbrella, no coat except my suit-coat–no one… Paris!!! I had an engagement to meet “the Czechoslovakian professor” and to go with him to the International Exposition of Decorative Arts. But I couldn’t find the address, and the taxi man took me to the wrong Hotel Angleterre… and I missed Ann for lunch again.11Paris Diary, Friday, June 26, 1925. Bennett, Gwendolyn. Gwendolyn Bennett Papers, 1916-1981. Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture, The New York Public Library. Reprinted in Bennett, Gwendolyn. Heroine of the Harlem Renaissance and beyond: Gwendolyn Bennett’s Selected Writings. Eds. Belinda Wheeler and Louis J. Parascandola. The Pennsylvania State University Press, 2018. p. 179.

Clutching her soggy map, she finds her way to the L’Ecole Des Arts Decoratif where they tell her that one must either be under 13 or over 26 years old to enroll. And she’s 23!!!!12Paris Diary, Tuesday, June 30, 1925. Bennett, Gwendolyn. Gwendolyn Bennett Papers, 1916-1981. Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture, The New York Public Library. It’s late in the afternoon. Her search will have to wait for another day. She is cold and heartsick… and nearly starved! And it rains…13Paris Diary, Friday, June 26, 1925. Bennett, Gwendolyn. Gwendolyn Bennett Papers, 1916-1981. Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture, The New York Public Library. Reprinted in Bennett, Gwendolyn. Heroine of the Harlem Renaissance and beyond: Gwendolyn Bennett’s Selected Writings. Eds. Belinda Wheeler and Louis J. Parascandola. The Pennsylvania State University Press, 2018. p. 179.

At night, desperate to relieve her loneliness, she goes to the cinema:

It is long and tiresome although the pictures in themselves are not bad. On the way home, I miscalculated my distance and I had not counted on the winding of the street. It was dark and I became afraid and thought I was lost. All the horrible things that I had heard about Paris came to my mind and I was almost panic stricken. Frantically, I ask each person I passed, “Ou la Rue D’Assas?” and they all give the same answer “la troisieme a gauche.”14Paris Diary, Friday, June 26, 1925. Bennett, Gwendolyn. Gwendolyn Bennett Papers, 1916-1981. Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture, The New York Public Library. Reprinted in Bennett, Gwendolyn. Heroine of the Harlem Renaissance and beyond: Gwendolyn Bennett’s Selected Writings. Eds. Belinda Wheeler and Louis J. Parascandola. The Pennsylvania State University Press, 2018. p. 179.

With her limited French, she doesn’t understand their meaning and can’t find her hotel. She is more frightened than she’s ever been.

Flashback: July 1902 – May 1925

It’s not that she hasn’t traveled before—her entire life has been a series of dislocations and relocations. She was born on July 8, 1902 in Giddings, Texas, to Joshua and Mayme Bennett, though there’s no record of her because the state of Texas didn’t bother to issue birth certificates to Black children at the time. Her family was always on the move, perhaps because of restlessness or because of job prospects, later for security reasons.15Govan, Sandra Y. Gwendolyn Bennett: Portrait of an Artist Lost. ProQuest Dissertations Publishing, 1980. p. 56

Her first memories are of the Paiute Indian Reservation in Wadsworth, Nevada, where her parents taught school. When she was four years old, the Bennett family moved to Washington D.C. Her father worked as a clerk in a government office and attended Howard University school of law at night, while her mother taught grade school and cared for her.

Ward Place, Washington D.C.—a street “across the tracks” and no doubt ugly, with brick pavements, unkempt, two-storied brick houses, and one or two wooden “stoops” before the front doors. But for her, Ward Place was a sweet, remembered place. Her mother would sew her clothes and curl her hair, topping it with an enormous red ribbon. She would dress “for the afternoon” in a red muslin frock with many fine ruffles, high-buttoned red shoes, and white stockings. Walking too and fro, she would wait for her father to come home for work.16Gwendolyn Bennett. “Ward Place.” Heroine of the Harlem Renaissance and beyond: Gwendolyn Bennett’s Selected Writings. Eds. Belinda Wheeler and Louis J. Parascandola. The Pennsylvania State University Press, 2018. p. 151.

Those halcyon days were soon clouded by stormy arguments between her parents about another woman. Her baby heart ached with the horror of what was happening.17Gwendolyn Bennett. “My Father’s Story.” Heroine of the Harlem Renaissance and beyond: Gwendolyn Bennett’s Selected Writings. Eds. Belinda Wheeler and Louis J. Parascandola. The Pennsylvania State University Press, 2018. p. 149. Clinging to her bed frame, listening to her parents quarrel, she screamed, “I hate that nasty Jeannette Carter!”18Gwendolyn Bennett. “Ward Place.” Heroine of the Harlem Renaissance and beyond: Gwendolyn Bennett’s Selected Writings. Eds. Belinda Wheeler and Louis J. Parascandola. The Pennsylvania State University Press, 2018. p. 153.

That was the end of her childhood, though she didn’t realize it at the time. When her parents divorced, her mother was granted custody and moved with her to a wealthy white girls’ finishing school on Connecticut Avenue—most likely the Chevy Chase School—where she could make more money as a live-in domestic worker and hairdresser. A vivacious child who could recite “Hiawatha” from start to finish, she was the darling of the school, as well as the apple of her father’s eye. When he took her out on Sundays and holidays, he made her feel like a princess.

With him I was person and he was a somebody, a promising young lawyer. We did all the things fondest to my heart. He took me to dinner with families where I played with the children of the family with no shadows to cross the horizon; we went to the theatre, to restaurants for dinner, we went for long car rides and to all sorts of places of amusement, we laughed and played together.19Gwendolyn Bennett. “My Father’s Story.” Heroine of the Harlem Renaissance and beyond: Gwendolyn Bennett’s Selected Writings. Eds. Belinda Wheeler and Louis J. Parascandola. The Pennsylvania State University Press, 2018. p. 150.

When she was eight years old, he took her to Mount Vernon and never brought her home. She didn’t see her mother again for sixteen years. Her father moved them from city to city in Pennsylvania, seeking legal work and evading detection. They’d stay a year in one place and then suddenly, with some engaging promise of newer, more exciting scenes, he would announce that they were going to a new city.20Gwendolyn Bennett. “Lancaster, Pa.” Heroine of the Harlem Renaissance and beyond: Gwendolyn Bennett’s Selected Writings. Eds. Belinda Wheeler and Louis J. Parascandola. The Pennsylvania State University Press, 2018. pp. 153-154.

Her long pilgrimage came to a close when she was 12 and her father married Marechal Neil.21Gwendolyn Bennett. “Lancaster, Pa.” Heroine of the Harlem Renaissance and beyond: Gwendolyn Bennett’s Selected Writings. Eds. Belinda Wheeler and Louis J. Parascandola. The Pennsylvania State University Press, 2018. p. 153. Though only seven years older, Marechal became the beloved mother-figure and confidante she longed for.

She takes me to her heart, although I am heartbroken that my prayer for reunion between mother & dad does not, cannot come true.22“Life Story” [outline], p. 11. Bennett, Gwendolyn. Gwendolyn Bennett Papers, 1916-1981. Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture, The New York Public Library.

Her new family of three took root at 64 Brooklyn Avenue in New York City. She attended a girls’ high school in Brooklyn, excelling as an artist, poet, playwright, and songwriter and graduating at the top of her class.

Gwendolyn Bennett at Columbia University, Summer 1924. Claude McKay Collection. Yale Collection of American Literature, Beinecke Rare Book and Manuscript Library.

She made her way to Harlem and enrolled at Columbia University to study art. At the 135th Street branch of the New York Public Library, she found a community of young artists and writers like herself. She befriended Langston Hughes, Harold Jackman, Jessie Fauset, Regina Anderson, Countee Cullen, and many other emerging talents. They were part of a new generation of Black artists, no longer beholden to stuffy white standards. Together, they were making art that was fresh, modern, and true.

July 1925

But now she is alone, far from family and friends and an ocean away from Harlem. She feels a longing for home that is kin to desolation.23Gwendolyn Bennett. Letter to Langston Hughes, Paris, France, 1926, p. 1. Langston Hughes Papers. James Weldon Johnson Collection in the Yale Collection of American Literature, Beinecke Rare Book and Manuscript Library. https://collections.library.yale.edu/catalog/16862301 Reprinted in Bennett, Gwendolyn. Heroine of the Harlem Renaissance and beyond: Gwendolyn Bennett’s Selected Writings. Eds. Belinda Wheeler and Louis J. Parascandola. The Pennsylvania State University Press, 2018, pp. 203-204. It almost feels like she doesn’t have a right to be in Paris.24Gwendolyn Bennett, letter to Langston Hughes, August 28, 1925. Qtd by Barton, Melissa. “Mondays at Beinecke: ‘All the news as well as the scandal’ – Gwendolyn Bennett’s letters from Paris with Melissa Barton.” Public Zoom Lecture. 6 Dec. 2021. https://library.yale.edu/event/mondays-beinecke-10)

But she mustn’t give into despair. She must get out, seize the opportunities, and focus her attention only on the high spots.25Paris Diary, Friday, June 26, 1925. Bennett, Gwendolyn. Gwendolyn Bennett Papers, 1916-1981. Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture, The New York Public Library. Reprinted in Bennett, Gwendolyn. Heroine of the Harlem Renaissance and beyond: Gwendolyn Bennett’s Selected Writings. Eds. Belinda Wheeler and Louis J. Parascandola. The Pennsylvania State University Press, 2018. p. 179.

I started down Blvd St-Michel, and had scarcely gone more than thirty yards when I passed a young, nice-looking colored girl. …We both turned around and she said with infections impulsiveness, “Are you from America?” And when I answered in the affirmative she said, “You’re not by any chance Gwendolyn Bennett.” And I answered, “Yes and are you Anne Causey?” …and she was. …She took me to see Gwendolyn Sinclair who is studying fashion drawing. From that moment on “les deux Gwendolyns” start in to search for a studio… and it’s a terrible task to say the least. …After dinner together, Gwendolyn and I continued our studio hunt, but all in vain.26Paris Diary, Monday, June 29, 1925. Bennett, Gwendolyn. Gwendolyn Bennett Papers, 1916-1981. Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture, The New York Public Library.

For days, she hunts high and low for studios or large rooms. And of course, there is nothing.27Paris Diary, Saturday, June 27, 1925. Bennett, Gwendolyn. Gwendolyn Bennett Papers, 1916-1981. Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture, The New York Public Library. One afternoon Aulston and his father accompany her to the Foyer on the Boulevard Raspail to see about a studio. Perhaps it will help to have men on the search. But there is none.28Paris Diary, Saturday, June 27, 1925. Bennett, Gwendolyn. Gwendolyn Bennett Papers, 1916-1981. Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture, The New York Public Library.

It might seem quite all right not to have a place to work but I am fired with a maddening desire to be up and at it. It is really quite killing…Not to be able to work when one has the will is worse than never having the will.29Paris Diary, Saturday, June 27, 1925. Bennett, Gwendolyn. Gwendolyn Bennett Papers, 1916-1981. Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture, The New York Public Library.

August 1925

Despite the frustration of not having a studio, she begins to acclimate to Paris life, attempting to master the French language, take in the rich artistic culture, develop her painting skills, and immerse herself in the nightlife of Paris in the Jazz Age.

Somewhere in the back of my mind there runs the knowledge that I registered in the College de La Guilde for French classes and that I was infinitely weary of hearing so much French and understanding so little! Finally, I gave it up—not because I was making a failure of it but chiefly because it consumed three marvelous morning hours and gave so little in return—and there is so much to be done!30Paris Diary, Sunday July 26, 1925. Bennett, Gwendolyn. Gwendolyn Bennett Papers, 1916-1981. Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture, The New York Public Library. Reprinted in Bennett, Gwendolyn. Heroine of the Harlem Renaissance and beyond: Gwendolyn Bennett’s Selected Writings. Eds. Belinda Wheeler and Louis J. Parascandola. The Pennsylvania State University Press, 2018. p. 180.

She seeks beauty and inspiration in the museums and cathedrals of Paris: Musée du Luxembourg, Le Salon, and St. Sulpice. One day, she walks all the way from the Quartier to the Musée des Arts Decoratifs and back. The museum is a marvelous thing. Just being able to see Corot’s palette and hat and Delacroix’s brush and pipe fires her with a new purpose to do and learn!31Paris Diary, Tuesday, June 30, 1925. Bennett, Gwendolyn. Gwendolyn Bennett Papers, 1916-1981. Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture, The New York Public Library.

She enrolls at the Académie de la Grande Chaumière with an enthusiasm that seems universal among those who come to Paris to study art.32Paris Diary, April 29, 1926. Bennett, Gwendolyn. Gwendolyn Bennett Papers, 1916-1981. Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture, The New York Public Library. Reprinted in Bennett, Gwendolyn. Heroine of the Harlem Renaissance and beyond: Gwendolyn Bennett’s Selected Writings. Eds. Belinda Wheeler and Louis J. Parascandola. The Pennsylvania State University Press, 2018. p. 185. She works hard all morning painting a nude in oil. It’s the first one she’s ever done, and the results are discouraging.33Paris Diary, Monday, August 3, 1925. Bennett, Gwendolyn. Gwendolyn Bennett Papers, 1916-1981. Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture, The New York Public Library.

Art is long!34Paris Diary, Monday, August 3, 1925. Bennett, Gwendolyn. Gwendolyn Bennett Papers, 1916-1981. Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture, The New York Public Library.

In time, she determines that French methods in teaching art are not the best and that the equipment in their schools is poor.35Paris Diary, April 29, 1926. Bennett, Gwendolyn. Gwendolyn Bennett Papers, 1916-1981. Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture, The New York Public Library. Reprinted in Bennett, Gwendolyn. Heroine of the Harlem Renaissance and beyond: Gwendolyn Bennett’s Selected Writings. Eds. Belinda Wheeler and Louis J. Parascandola. The Pennsylvania State University Press, 2018. p. 185. She still has no studio to work in.

Connecting with other Black artists in Paris brings her great joy, easing the throbbing pangs of discouragement, self-doubt, and homesickness. She listens to Louis Jones play violin accompanied by a Mr. Callilaux and it makes her heart swell with pride to know these musicians who are black and yet so wonderful. In the evening, she enjoys much laughter and fun at the Hotel Corneille with Thelma, Charlotte, and Betty.36Paris Diary, August 2, 1925. Bennett, Gwendolyn. Gwendolyn Bennett Papers, 1916-1981. Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture, The New York Public Library. Reprinted in Bennett, Gwendolyn. Heroine of the Harlem Renaissance and beyond: Gwendolyn Bennett’s Selected Writings. Eds. Belinda Wheeler and Louis J. Parascandola. The Pennsylvania State University Press, 2018. p. 181. The next week, she joins a larger group for a glorious night starting out at a Chinese restaurant, thence to “Le Royal” in Montmartre, where there is much champagne and many cigarettes and much dancing…37Paris Diary, August 8, 1926. Bennett, Gwendolyn. Gwendolyn Bennett Papers, 1916-1981. Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture, The New York Public Library. Reprinted in Bennett, Gwendolyn. Heroine of the Harlem Renaissance and beyond: Gwendolyn Bennett’s Selected Writings. Eds. Belinda Wheeler and Louis J. Parascandola. The Pennsylvania State University Press, 2018. p. 181.

Then at 4:15 a.m. to dear old Bricktop’s. The Grand Duc extremely crowded with our folk. Lottie Gee there on her first night in town and sings for “Brick” her hit from “Shuffle Along”—”I’m Just Wild About Harry.” Her voice is not what it might have been and she had too much champagne, but still there was something very personal and dear about her singing and we colored folks just applauded like mad.38Paris Diary, August 8, 1926. Bennett, Gwendolyn. Gwendolyn Bennett Papers, 1916-1981. Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture, The New York Public Library. Reprinted in Bennett, Gwendolyn. Heroine of the Harlem Renaissance and beyond: Gwendolyn Bennett’s Selected Writings. Eds. Belinda Wheeler and Louis J. Parascandola. The Pennsylvania State University Press, 2018. p. 181.

There’s a ‘Revue Negre’ in town, which she will go to in a day or two. The white folks have gone wild about it. It has received wonderful reviews in the papers.39Gwendolyn Bennett, Letter to Harold Jackman, October 27, 1925, pp. 2-3. Bennett, Gwendolyn B., 5 autograph letters and 1 typed letter, signed, to Harold Jackman. James Weldon Johnson Collection in the Yale Collection of American Literature, Beinecke Rare Book and Manuscript Library. https://collections.library.yale.edu/catalog/16867529 Paris is Charleston mad.40Gwendolyn Bennett, Letter to Harold Jackman, February 25, 1926. Bennett, Gwendolyn B., 5 autograph letters and 1 typed letter, signed, to Harold Jackman. James Weldon Johnson Collection in the Yale Collection of American Literature, Beinecke Rare Book and Manuscript Library. https://collections.library.yale.edu/catalog/16867529

Some visiting Americans take her to see Thaïs, a French opera by Jules Massenet, based on the novel of the same title by Anatole France. She will never forget the beautiful “Meditation” as played by the wonderful orchestra:41Paris Diary, Sunday, August 2, 1926. Bennett, Gwendolyn. Gwendolyn Bennett Papers, 1916-1981. Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture, The New York Public Library.

Massenet, Jules, Mischa Elman, and Josef Bonime. Meditation. 1919. Audio. Retrieved from the Library of Congress, <www.loc.gov/item/jukebox-290619/>.

This is my first experience at Opera …and oh how, I love it. I wish that I could crowd all of them into my heart during these few swift months that I shall be here. Money is so necessary to make a place for beauty. Today when I so want to live and learn I am filled with sorrow to feel that money keeps me from so much.42Paris Diary, Sunday, August 2, 1926. Bennett, Gwendolyn. Gwendolyn Bennett Papers, 1916-1981. Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture, The New York Public Library.

September 1925

Things go rather slowly.43Gwendolyn Bennett, Letter to Harold Jackman, September 20, 1925. Bennett, Gwendolyn B., 5 autograph letters and 1 typed letter, signed, to Harold Jackman. James Weldon Johnson Collection in the Yale Collection of American Literature, Beinecke Rare Book and Manuscript Library. https://collections.library.yale.edu/catalog/16867529 She still hasn’t found an art school that satisfies her. Fortunately, art schools in Paris are free—and open to Negroes—which is not the case in America. She decides to try the Academie Julian. It is considered one of the best art schools in the world and is where Tanner went when he first came to Europe.44Gwendolyn Bennett, Letter to Harold Jackman, September 20, 1925. Bennett, Gwendolyn B., 5 autograph letters and 1 typed letter, signed, to Harold Jackman. James Weldon Johnson Collection in the Yale Collection of American Literature, Beinecke Rare Book and Manuscript Library. https://collections.library.yale.edu/catalog/16867529

October 1925

I am attending the Academie Julian and like it very much. I work there in the mornings and at the Académie Colarossi in the afternoon. I write on Sundays and two nights a week. My life is fairly well regulated and I keep quite busy.45Gwendolyn Bennett, Letter to Harold Jackman, October 27, 1925. Bennett, Gwendolyn B., 5 autograph letters and 1 typed letter, signed, to Harold Jackman. James Weldon Johnson Collection in the Yale Collection of American Literature, Beinecke Rare Book and Manuscript Library. https://collections.library.yale.edu/catalog/16867529

November 1925

Paul and Essie Robeson arrive, enabling her to horn in on all the wonderful places to which they are invited—teas at Sylvia Beach’s and at Gertrude Stein’s salon where of course everybody is there.46Gwendolyn Bennett. Letter to Langston Hughes, December 2, 1925. Langston Hughes Papers. James Weldon Johnson Collection in the Yale Collection of American Literature, Beinecke Rare Book and Manuscript Library. https://collections.library.yale.edu/catalog/16862301 Reprinted in Bennett, Gwendolyn. Heroine of the Harlem Renaissance and beyond: Gwendolyn Bennett’s Selected Writings. Eds. Belinda Wheeler and Louis J. Parascandola. The Pennsylvania State University Press, 2018, pp. 198-200. Henri Matisse’s home is like going to a holy shrine.47Gwendolyn Bennett, Letter to Harold Jackman, February 25, 1926. Bennett, Gwendolyn B., 5 autograph letters and 1 typed letter, signed, to Harold Jackman. James Weldon Johnson Collection in the Yale Collection of American Literature, Beinecke Rare Book and Manuscript Library. https://collections.library.yale.edu/catalog/16867529 Reprinted in Bennett, Gwendolyn. Heroine of the Harlem Renaissance and beyond: Gwendolyn Bennett’s Selected Writings. Eds. Belinda Wheeler and Louis J. Parascandola. The Pennsylvania State University Press, 2018, pp. 198-200. She feels very much the Cinderella sans slipper. Sylvia Beach very sweetly invites her to have Thanksgiving dinner in her home.48Gwendolyn Bennett. Letter to Langston Hughes, December 2, 1925. Langston Hughes Papers. James Weldon Johnson Collection in the Yale Collection of American Literature, Beinecke Rare Book and Manuscript Library. https://collections.library.yale.edu/catalog/16862301 Reprinted in Bennett, Gwendolyn. Heroine of the Harlem Renaissance and beyond: Gwendolyn Bennett’s Selected Writings. Eds. Belinda Wheeler and Louis J. Parascandola. The Pennsylvania State University Press, 2018, pp. 198-200. The Robesons introduce her to Konrad Bercovici and his family, and she becomes the best of friends with Rada, the older daughter.49Gwendolyn Bennett, Letter to Harold Jackman, January 11, 1926. Bennett, Gwendolyn B., 5 autograph letters and 1 typed letter, signed, to Harold Jackman. James Weldon Johnson Collection in the Yale Collection of American Literature, Beinecke Rare Book and Manuscript Library. https://collections.library.yale.edu/catalog/16867529 They insist that she eat a meal at their place every other day, and she grows more and more fond of them.50Gwendolyn Bennett. Letter to Langston Hughes, December 2, 1925. Langston Hughes Papers. James Weldon Johnson Collection in the Yale Collection of American Literature, Beinecke Rare Book and Manuscript Library. https://collections.library.yale.edu/catalog/16862301

I’m beginning to people my world with the same kind of ‘regular’ folks I knew in New York only none of them are colored. Queer, this! 51Gwendolyn Bennett, Letter to Harold Jackman, October 27, 1925. Bennett, Gwendolyn B., 5 autograph letters and 1 typed letter, signed, to Harold Jackman. James Weldon Johnson Collection in the Yale Collection of American Literature, Beinecke Rare Book and Manuscript Library. https://collections.library.yale.edu/catalog/16867529

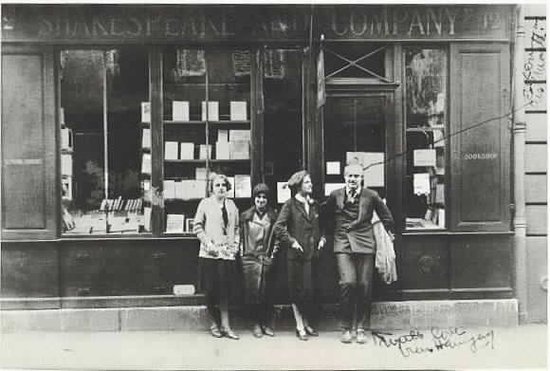

She moves to 13 Carrefour de L’Odeon, just down the road from Sylvia Beach’s bookstore Shakespeare & Company. She stops by the bookstore almost daily: it’s a warm, cheerful place where she can hobnob with other writers and read American magazines like the Little Review and the Mercury. She hits it off with Ernest Hemingway—a charming fellow—big and blustery with an out-doors quality about him coupled with a boyishness that makes him just right.52Gwendolyn Bennett, Letter to Harold Jackman, January 11, 1926. Bennett, Gwendolyn B., 5 autograph letters and 1 typed letter, signed, to Harold Jackman. James Weldon Johnson Collection in the Yale Collection of American Literature, Beinecke Rare Book and Manuscript Library. https://collections.library.yale.edu/catalog/16867529 When she mentions a Boni and Liveright prize for the best work by a Negro writer, he says, “Gee, I wish I were a Negro. I could use a thousand dollar prize.”53Qtd by Sandra Y. Govan, Gwendolyn Bennett: Portrait of an Artist Lost. ProQuest Dissertations Publishing, 1980. p. 73.

Despite her lively social life, she hates missing out on all the happenings in Harlem. FOMO is real. She writes to Harold, Langston, Countee, Regina, and Jessie, begging them: send all the news as well as the scandal.54Gwendolyn Bennett, Letter to Harold Jackman, September 20, 1925. Bennett, Gwendolyn B., 5 autograph letters and 1 typed letter, signed, to Harold Jackman. James Weldon Johnson Collection in the Yale Collection of American Literature, Beinecke Rare Book and Manuscript Library. https://collections.library.yale.edu/catalog/16867529

December 1925

I am working hard and writing has played a great part in that work. I have sent off twelve things to Opportunity for the contest. Pray with me that I win something. It’s a shame to say so but I do hope that neither Countee nor Langston enter anything as I would stand little or no chance if they did. …If I win no prize, I shall know for a certainty that I cannot write… so you see much hangs on this… I have sent about ten poems to American magazines. Some of them I have not heard from as yet. I have received five of them back so far. Splendid, isn’t it? All I need to do is to get one poem published in a good white magazine to make me have real confidence in myself.55Gwendolyn Bennett, Letter to Harold Jackman, January 11, 1926. Bennett, Gwendolyn B., 5 autograph letters and 1 typed letter, signed, to Harold Jackman. James Weldon Johnson Collection in the Yale Collection of American Literature, Beinecke Rare Book and Manuscript Library. https://collections.library.yale.edu/catalog/16867529

January 1926

She doesn’t win the contest or land a poem in a white magazine, but has a new reason to celebrate:

I HAVE A STUDIO!!!!!! Hurrah!!!!!! After seven weary months of knocking about here and there, I had come to the conclusion that finding a studio was an utter impossibility. And then just swish and I have one… It is a lovely place … just like a nice homely stable.56Gwendolyn Bennett. Letter to Langston Hughes, Paris, France, 1926. Langston Hughes Papers. James Weldon Johnson Collection in the Yale Collection of American Literature, Beinecke Rare Book and Manuscript Library. https://collections.library.yale.edu/catalog/16862301

…Gee, I wish some of my gang from New York was here so we could have a real party. The studio is the peachiest place ever….rue de la Tour d’Auvergne just on the outskirts of Montmartre. I am as happy as a lark. Now I can do some real work. I am working hard on the things for my home-coming exhibition.57Gwendolyn Bennett, Letter to Harold Jackman, February 25, 1926. Bennett, Gwendolyn B., 5 autograph letters and 1 typed letter, signed, to Harold Jackman. James Weldon Johnson Collection in the Yale Collection of American Literature, Beinecke Rare Book and Manuscript Library. https://collections.library.yale.edu/catalog/16867529

February 1926

She never knows when she will have to move, and now, with little warning, she has to move out of 133 Carrefour de L’Odeon. The peculiar circumstances that are neither that she has been put out or that she can’t pay her rent, but she doesn’t want to say more. She leaves no forwarding address. Certain things about her moving of a sudden make it rather uncomfortable for her to go back to see about the mail, so she can’t find out if the copy of The New Negro Harold sent arrived there.58Gwendolyn Bennett, Letter to Harold Jackman, February 25, 1926. Bennett, Gwendolyn B., 5 autograph letters and 1 typed letter, signed, to Harold Jackman. James Weldon Johnson Collection in the Yale Collection of American Literature, Beinecke Rare Book and Manuscript Library. https://collections.library.yale.edu/catalog/16867529 It’s an expensive book and she has been waiting for it for months.

Damn! That’s the only world I know that fits the situation.59Gwendolyn Bennett, Letter to Harold Jackman, February 25, 1926. Bennett, Gwendolyn B., 5 autograph letters and 1 typed letter, signed, to Harold Jackman. James Weldon Johnson Collection in the Yale Collection of American Literature, Beinecke Rare Book and Manuscript Library. https://collections.library.yale.edu/catalog/16867529

March 1926

At least she has the studio, where in addition to painting, she works in batik, a craft she selected as her speciality when she studied at the Pratt Institute. Her mentor Charles Johnson has made a connection for her with Miss Grace Drake of the fashionable Gown Shop in New York City, who will sell her batiks (minus a small commission) as fast as she can find the leisure or inclination to supply them.60Paris Diary, Thursday, October 1, 1925. Bennett, Gwendolyn. Gwendolyn Bennett Papers, 1916-1981. Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture, The New York Public Library. Not only can she make much needed money, but she also feels more free to experiment in batik than in oils, perhaps because there isn’t such a monumental European tradition to measure herself against.

I too like the moderns although I do not feel that I myself am one…..at any rate not in painting. My batiks are more so. This year in Paris has been a revelation to me as far as modern work is concerned.61Gwendolyn Bennett, Letter to Harold Jackman, February 23, 1926. Bennett, Gwendolyn B., 5 autograph letters and 1 typed letter, signed, to Harold Jackman. James Weldon Johnson Collection in the Yale Collection of American Literature, Beinecke Rare Book and Manuscript Library. https://collections.library.yale.edu/catalog/16867529 Reprinted in Bennett, Gwendolyn. Heroine of the Harlem Renaissance and beyond: Gwendolyn Bennett’s Selected Writings. Eds. Belinda Wheeler and Louis J. Parascandola. The Pennsylvania State University Press, 2018, pp. 201-202.

April 1926

Her painting and batik-making are going well:

I am working like Hades to get my exhibition ready for my home-coming. I hope to make it a hum-dinger in every sense of the word. …I should love to be able to have something really worthwhile to send off.

…I am sailing the first week of June, oh boy! I shall be so glad to get back I wont know what to do. It seems years since I was last there. It will certainly be good to to be back where I “belong.” I have loved being here this year and would not have given anything for it but still there is that “homeward tug” about which poets sing.62Gwendolyn Bennett, Letter to Harold Jackman, April 15, 1926. Bennett, Gwendolyn B., 5 autograph letters and 1 typed letter, signed, to Harold Jackman. James Weldon Johnson Collection in the Yale Collection of American Literature, Beinecke Rare Book and Manuscript Library. https://collections.library.yale.edu/catalog/16867529

…Just think being among folks you really know and care about…….aint it a grand and glorious feeling?63Gwendolyn Bennett, Letter to Harold Jackman, February 25, 1926. Bennett, Gwendolyn B., 5 autograph letters and 1 typed letter, signed, to Harold Jackman. James Weldon Johnson Collection in the Yale Collection of American Literature, Beinecke Rare Book and Manuscript Library. https://collections.library.yale.edu/catalog/16867529

July 1926

Back in Harlem, she reconnects with her pals, bumming around together like old times. She gets caught in a whirlwind of activities. Her mentor Charles Johnson offers her employment as assistant to the editor at Opportunity and agrees to publish her idea for literary-arts column she will call “The Ebony Flute”—a “chit chat and what not” that will allow her to keep track of the comings and goings of Negro writers, artists, and performers. She inquires about terms for her homecoming exhibition at Clara Payne Whitney’s studio and asks Vivienne Stoner for help finding a gallery in the Village. The Harlem streets sizzle in the summer heat, and she, Langston, Wally, and Zora cook up a plan for their own magazine, Fire!! A Magazine of the Younger Negro Artists.

August 13, 1926

Her plans are derailed when her father plunges to his death under a subway train. She sees it happen, across the tracks and out of reach, as crowds mill about the dusty platform. Did he fall or jump? It hardly makes a difference, as he had already fallen from grace in her eyes a year ago, when she learned the shocking truth about his affair with Clara Hicks—his former clerk and her former student, who was just 17 years old when it all began—not to mention the charges against him for embezzlement and malpractice. He’d promised to reform his ways, writing to her in Paris with reassurances that he was “retrieving himself, rehabilitating a heretofore seemingly discordant and decadent ‘Daddy’; making a Dad worthy of his dear Baby’s reverent love, confidence, respect.”64Joshua Bennett, Letter to “Dear Dad” [Joshua Bennett], October 26, 1925, p. 3. Bennett, Joshua and Marechal. Gwendolyn Bennett Papers. Yale Collection of American Literature, Beinecke Rare Book and Manuscript Library. https://collections.library.yale.edu/catalog/16817908 But it turns out that those words were just more lies and fabrications.

To say that I was surprised and ashamed is to put it mildly.65Gwendolyn Bennett, Letter to “Dear Dad” [Joshua Bennett], May 17, 1925. Bennett, Joshua and Marechal. Gwendolyn Bennett Papers. Yale Collection of American Literature, Beinecke Rare Book and Manuscript Library. https://collections.library.yale.edu/catalog/16817908

The newspapers buzz with the scandalous “tale of mystery, love and tragedy,” exposing lurid details of his private life, quoting his impassioned love letters to Clara, and never failing to mention that he was “the father of the distinguished art teacher and writer Gwendolyn Bennett.”66“Eastern Social Circles Agog Over Bennett’s Suicide,” The Pittsburgh Courier, August 28, 1926, p. 3. He leaves her saddled with debts, tangled in a legal morass, and mired in a pit of grief, anger, and shame.

September 1926

She has to move again, this time to Howard University, to resume a teaching position that pays little—certainly not enough to lift her out of debt—yet eats up all her time and energy.

Here at Howard you only get paid twenty dollars per pupil for the whole space of twelve weeks. I only happen to have four pupils, which will be only eighty dollars. Do the division in this problem and you’ll have just what my salary per hour amounts to. I teach in the evening from five thirty until nine thirty. …Three days a week I teach all day from nine til five and then return to teach night school at night. The other days I am through at 12 oclock.67Gwendolyn Bennett, Letter to “Dearest Mumsey” [Marechal Bennett], March 24, 1925. Bennett, Joshua and Marechal. Gwendolyn Bennett Papers. Yale Collection of American Literature, Beinecke Rare Book and Manuscript Library. https://collections.library.yale.edu/catalog/16817908 Reprinted in Bennett, Gwendolyn. Heroine of the Harlem Renaissance and beyond: Gwendolyn Bennett’s Selected Writings. Eds. Belinda Wheeler and Louis J. Parascandola. The Pennsylvania State University Press, 2018, p. 215.

Before she goes back to Washington, she stashes the paintings she brought back from Paris in her stepmother Marechal’s basement, along with her art supplies—paints, brushes, canvases, funnel and dipper pens, tjantings and tjaps—taking only the batiks with her. She had been using the basement as a makeshift New York studio. Her stepmother did not approve of her using kitchen pots for dyes, especially when they turned the mashed potatoes green. Not long after she leaves for Howard, a fire breaks out in the basement, destroying all her artwork and supplies.68Sandra Y. Govan recounts this incident in Gwendolyn Bennett: Portrait of an Artist Lost. ProQuest Dissertations Publishing, 1980, p. 82.

October 1926

Financial woes consume her. Almost all her letters to Marechal concern money owed, promised, begged, and borrowed—$27.46 for the telephone, $3.50 for a dress at the cleaner’s.69Gwendolyn Bennett, letters to Marechal Bennett, Joshua and Marechal. Gwendolyn Bennett Papers. Yale Collection of American Literature, Beinecke Rare Book and Manuscript Library. https://collections.library.yale.edu/catalog/16817908 There’s never enough to cover even meager household expenses, she cannot sleep, and her hair is falling out with all the worry.

I can’t go on this way…I am worrying myself almost crazy—three more spots have dropped out of my head, each of them about the size of a quarter and I scarcely sleep a wink at night. In spite of this I am trying to write stories and articles and what-not and trying to sell them wherever I can…it’s pretty hard though, for they continue to be returned.70Gwendolyn Bennett, Letter to “Mumsey Darling” [Marechal Bennett], Wednesday Morning Early, n.d. Bennett, Joshua and Marechal. Gwendolyn Bennett Papers. Yale Collection of American Literature, Beinecke Rare Book and Manuscript Library. https://collections.library.yale.edu/catalog/16817908

If only she could afford a studio of her own like the one she had in Paris. But she needs more than a studio—she needs art supplies, space to store her work, time to create it, and, more than anything else, a community of artists to inspire and urge her on. Washington, DC, is a God-forsaken place.71Gwendolyn Bennett, Letter to “Dearest Mumsey and Daddy” [Marechal and Joshua Bennett], Monday, January 5, 1925. Bennett, Joshua and Marechal. Gwendolyn Bennett Papers. Yale Collection of American Literature, Beinecke Rare Book and Manuscript Library. https://collections.library.yale.edu/catalog/16817908 The genteel Negro society cares far more about fine clothes, alcohol, and parties than about books, art, and ideas.

I am in a dry land where no water is…. Barren fields are as dry as dust.72Gwendolyn Bennett, Letter to Carl Van Vechten, Wednesday Morning, n.d. [1926] Carl Van Vechten Papers Relating to African American Arts and Letters. James Weldon Johnson Collection in the Yale Collection of American Literature, Beinecke Rare Book and Manuscript Library. https://collections.library.yale.edu/catalog/16820216

November 1926

She is late submitting her monthly “Ebony Flute” column, but sends it off in the nick of time with apologies and the usual excuses. Fire!! ought to be out any minute now. She is terribly excited about it and hopes it is a success. She wants to go to New York for the weekend but if she can’t get a ride, she won’t go. She is absolutely broke.73Gwendolyn Bennett, Letter to Carl Van Vechten, November 15, 1926. Carl Van Vechten Papers Relating to African American Arts and Letters. James Weldon Johnson Collection in the Yale Collection of American Literature, Beinecke Rare Book and Manuscript Library. https://collections.library.yale.edu/catalog/16820216

June 1927

A gift and gown shop in Washington, DC, hosts a special exhibition of her textile arts—hand-painted gowns, scarfs and handkerchiefs, and batik wall hangings. It’s not an official gallery and spans only two days, but it’s the best she can manage. The only record of the exhibition is a small advertisement pasted in her scrapbook:74Scrapbook. Gwendolyn Bennett Papers, 1916-1981. Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture, The New York Public Library.

Winter 1928

She and Aaron Douglas win fellowships to study art at the prestigious Barnes Foundation in Merion, Pennsylvania, which has an extensive collection of African and modern art. She had been granted the fellowship a few years earlier but it was rescinded. At the time she was outraged, complaining to Alain Locke:

Something in me snapped when that fell through… There is something wrong with the justice of things when men like Barnes refuse me “a place in the sun” simply because I am a woman. But this is just one more broken illusion. I shall get over it before long!75Qtd by Sandra Y. Govan, Gwendolyn Bennett: Portrait of an Artist Lost. ProQuest Dissertations Publishing, 1980. p. 79.

She steps over the shards of her broken illusions, puts the injustice behind her, and re-applies. The fellowship gives her free access to the collection and $100 monthly stipend. It isn’t enough to live on, but it’s something to be proud of.

Spring 1928

She falls in love with Alfred Jackson, a medical student at Howard University. Fraternizing with students, even if they’re not in her classes, is forbidden. To preclude scandal, she resigns her position as Instructor of Art. Under the headline, “Art Weds Science,” the Pittsburgh Courier announces their wedding as if it’s something from a fairytale or novel: “Dr. Jackson and his bride are pursuing their respective studies; nevertheless they will struggle hand in hand for the success that must surely crown such ambitious, accomplished and deserving representatives of the new Negro!”76“Art Weds Science: Gwendolyn Bennett Becomes the Bride of Dr. Alfred J. Jackson. The Pittsburgh Courier, City Edition. 28 Apr 1928, p. 6.

Fall 1928

She moves to Eustis, Florida, so her new husband can launch a medical practice in his hometown. It is a good-sized town about 32 1/2 miles from Orlando. They have no colored doctor and are sadly in need of one.77Gwendolyn Bennett, Letter to “Mumsey dear” [Marechal Bennett], July 27, 1928. Gwendolyn Bennett Papers, 1916-1981. Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture, The New York Public Library. Reprinted in Heroine of the Harlem Renaissance, pp. 217-218. They live on a marvelously paved street—McDonald Avenue—but there’s no street number because mail isn’t delivered to the colored section.78Gwendolyn Bennett, Letter to “Mumsey Darling” [Marechal Bennett], February 15, 1929. Gwendolyn Bennett Papers, 1916-1981. Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture, The New York Public Library.

This is the South and Negroes have no privileges here.79Gwendolyn Bennett, Letter to “Mumsey Darling” [Marechal Bennett], February 15, 1929. Gwendolyn Bennett Papers, 1916-1981. Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture, The New York Public Library.

She gives up her beloved “Ebony Flute” column: there’s no way to keep track of developments in Black arts from Eustis, where there’s no arts community whatsoever. She teaches desultory students at Curtwright High School, a campus opened in 1925 to serve Negro students when the three-room school and two teachers proved insufficient. She role plays, doing all the things expected of a country house-wife.80Gwendolyn Bennett, Letter to “Mumsey Darling” [Marechal Bennett], January 23, 1929. Gwendolyn Bennett Papers, 1916-1981. Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture, The New York Public Library. She gains 69 pounds the first year.81Qtd by Sandra Y. Govan, Gwendolyn Bennett: Portrait of an Artist Lost. ProQuest Dissertations Publishing, 1980. p. 85.

The racism in Florida is like nothing she’s ever encountered: she is barred from the public library and terrorized by a KKK night ride.

I had never really believed it actually happened except in the far days following the Civil War, in distasteful moving pictures, and in books about the “Romantic South.” Until some fifty yards from the front of our house comes the ghostly cavalcade, driving in fearful, hooded silence up the one paved street in the Negro district of town. …When they were just about opposite the front door of our house, they came to a stop. …Their white robes were grotesque as they come across the wide street to our front yard. There must have been a dozen hooded Klansman stepping onto the little rise of ground… The first Klansman turned making a gesturing motion with his clumsy sheeted hand…We could translate his unspoken words, “This is the place.” Why didn’t we move? Where would we have gone even had we been able to move?82Gwendolyn Bennett, [Ku Klux Klan Rides], n.d., Heroine of the Harlem Renaissance and beyond: Gwendolyn Bennett’s Selected Writings. Eds. Belinda Wheeler and Louis J. Parascandola. The Pennsylvania State University Press, 2018. pp. 162-165.

In the same fall that she struggles to come to terms with oppressive norms of racism and sexism in the American South, Virginia Woolf delivers invited lectures on the topic of “women and fiction” at Newnham College and Girton College, the only women’s colleges at Cambridge University at the time.

1929

While she labors to manage a home, adjust to a disappointing marriage, and sustain her writing career, Virginia Woolf publishes A Room of One’s Own, an extended essay based on lectures she delivered the previous fall. Her visionary feminist manifesto comes to the “prosaic” yet revolutionary conclusion that:

it is necessary to have five hundred a year and a room with a lock on the door if you are to write fiction or poetry. (105)

> Virginia Woolf, A Room of One’s Own (1929)

A woman needs space and money to free her imagination from the fetters of worry, family obligations, fear, self-doubt, and anger. Only then can she achieve the “incandescent mind, like Shakespeare’s mind”—a mind with “no obstacle in it, no foreign matter unconsumed.”83Virginia Woolf. A Room of One’s Own. Foreword by Mary Gordon. San Diego, New York, and London: Harcourt Brace & Company, 1981. p. 56.

Woolf’s own mind seems incandescent as she illuminates the obstacles facing aspiring women writers—white, upper middle-class women, that is. She’s not concerned with working class women laboring in factories or sculleries, and she certainly isn’t thinking about a middle-class Black woman aspiring to become a great artist—the kind of person she mentions, in passing, as “a very fine negress.”84Virginia Woolf. A Room of One’s Own. Foreword by Mary Gordon. San Diego, New York, and London: Harcourt Brace & Company, 1981. p. 50. To her credit, she acknowledges the gift of financial independence bequeathed by her “aunt’s legacy,” which “unveiled the sky” to her.85Virginia Woolf. A Room of One’s Own. Foreword by Mary Gordon. San Diego, New York, and London: Harcourt Brace & Company, 1981. p. 39. But she seems unaware of how much harder it is for a Black woman to remove the veil.

W. E. B. Du Bois counsels that the veil is a fundamental condition of being Black in America:

…the Negro is…born with a veil and gifted with second-sight in this American world—a world which yields him no true consciousness, but only lets him see himself through the revelation of the other world. It is a peculiar sensation, this double consciousness, this sense of always looking at one’s self through the eyes of others, of measuring one’s soul by the tape of a world that looks on in amused contempt or pity.86W. E. B. Du Bois. The Souls of Black Folk. Ed. by Henry Louis Gates Jr. and Terri Hume Oliver. New York and London: W. W. Norton & Co., 1999. pp. 10-11

> W. E. B. Du Bois, The Souls of Black Folk (1903)

She has measured her soul by that tape all too often and come up wanting—and wanting more.

If a white Englishwoman requires a room of her own and 500 pounds per annum to write, what does it take for an African American woman to become an artist? How many more obstacles stand in her way? Audre Lorde will take up these questions half a century later:

A room of one’s own may be a necessity for writing prose, but so are reams of paper, a typewriter, and plenty of time. The actual requirements to produce the visual arts also determine, along class lines, whose art is whose. In this day of inflated prices for materials, who are our sculptors, our painters, our photographers? When we speak of broadly based women’s culture, we need to be aware of the effect of class and economic differences.87Audre Lorde, “Age, Race, Class, and Sex: Women Redefining Difference,” Sister Outsider. Crossing Press, 2007. p. 116.

> Audre Lorde, “Age, Race, Class, and Sex” (1980)

Struggling to run a household, support her husband’s medical practice, and work as a public schoolteacher, she doesn’t have the room, money, time, or mental space to paint or write:

I am intolerably busy! My life is actually so full; my duties are really so numerous; my burdens are so many and so new that when there is a quarter or an hour or so in which I could write…I have to stop and breathe or rest or else I feel the walls of my brain will crush in.

What I have done today is a fair sample of what one of my easy days is: I arose at 6:30 after a very fitful night of sleep, cooked breakfast (a real southern breakfast because that’s what Jack requires), served it; cooked almost an equal amount over again for my puppy and kitty (more about them later on); made up the bed, straightened around the house and washed the dishes; left so as to be in school at 8:15; from 8:15 until 3:15 taught every period except noon and I coached a basket-ball team at noon. And when you say “taught,” I mean every bit of that—the children are stupid and disinterested and entirely lacking in background. Why, when you stop to think of all the different things on which my mind must rest intently, it’s a wonder Idon’t go insane—Spanish, Ancient History, Drawing, Chemistry, Modern European History, Drawing, Gym work & basket-ball, Latin, General Science and English. Then at the end of it all, Jack was out on a call and didn’t come for me at the close of school and I had to walk part of the way home. When I got home, I worked around some nasturtiums & sweet peas I planted some time ago and watered them; thence I had to go to town with Jack on business—that took about an hour and a half. I then… got into my vegetable garden—my things are coming up well and need great care for the ground is sandy and dry here. I hoed for about an hour and set out three rows of collards. Then the telephone rang and Jack got a call to Zellwood (10 miles away)—I always go on long calls like that especially when it is near night-fall because going through these woods alone is too lonely and dangerous.88Gwendolyn Bennett, Letter to “Mumsey Darling” [Marechal Bennett], January 23, 1929. Gwendolyn Bennett Papers, 1916-1981. Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture, The New York Public Library.

The call rushed us so we didn’t have time to eat dinner at home — stopped in a little, dinky restaurant and ate some rotten food. Jack stayed on the call until quarter to nine… I wasn’t doing a thing but sitting in the car waiting but I was miles from home and in the dark so writing was out of the question. We rushed back to Eustis and get here about 9:30 and didn’t even go home but went straight to the school-house to basket-ball practice. On the way back two patients hailed Jack. Got home to find my pets starving—had eaten nothing since early morning—cooked them something. Stopped one half-hour to take inventory of the day with Jack and it is now two minutes to twelve o’clock. I must arise at six in the morning as I must hem up a dress to wear to school.89Gwendolyn Bennett, Letter to “Mumsey Darling” [Marechal Bennett], January 23, 1929. Gwendolyn Bennett Papers, 1916-1981. Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture, The New York Public Library.

Woolf argues that women writers need “shelter from the claims and tyrannies of their families.”90Virginia Woolf. A Room of One’s Own. Foreword by Mary Gordon. San Diego, New York, and London: Harcourt Brace & Company, 1981. p. 52. It certainly would be nice to have relief from all her domestic responsibilities. But she, who has moved so often and whose family has been fractured again and again, longs for a secure, stable family life. At the same time, she worries about how to balance her career goals with family obligations, especially if she gets pregnant.

Speaking about babies—I halfway thought I was going to have a little piece of the same kind of news to tell you but it has changed. I have been home sick in bed all this week, and since I was scheduled to have menstruated last Saturday and did not, I was positive that I was going to be able to confide in the baby’s grandmother—Ha. Ha. But I suppose it was due to the very heavy cold I have that the time was delayed, because everything came around all right last night. I was quite reconciled to the fact of being pregnant although I had set such store on finishing up my degree before I have a baby. But I think everything considered I have done well to go this long, don’t you?91Gwendolyn Bennett, Letter to “Mumsey Darling” [Marechal Bennett], February 15, 1929. Gwendolyn Bennett Papers, 1916-1981. Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture, The New York Public Library.

Woolf doesn’t say much about maternity and childcare, other than to acknowledge the “many other women” who are absent from her university lecture because “they are washing up the dishes and putting the children to bed.”92Virginia Woolf. A Room of One’s Own. Foreword by Mary Gordon. San Diego, New York, and London: Harcourt Brace & Company, 1981. p. 113. For both British and American women in the 1920s, motherhood may be the biggest obstacle to higher education and a writing career.

The situation is even harder for painters than writers, Woolf admits. Women novelists can silence the critical voices admonishing, “You cannot do this, you are incapable of doing that,” because they have many models of success—Jane Austen, George Eliot, Elizabeth Gaskell, and, she might add, Jessie Fauset. “But for painters it must still have some sting in it.”93Virginia Woolf. A Room of One’s Own. Foreword by Mary Gordon. San Diego, New York, and London: Harcourt Brace & Company, 1981. p. 54. She has so few role models, and she’s not the kind of genius who can work in isolation. She needs intellectual and artistic community, a receptive audience, and an artistic tradition to support her. The material costs are equally prohibitive: oil paints and canvases are expensive. A studio of her own is an impossibility. Even renting a typewriter presents problems:

Jack gets real mad at me because I had him rent a typewriter so I could write—I have things I have to send to New York and I am still trying to do it from Florida. He says “You haven’t written anything on it. We need money. Why don’t you earn some more money? You were a writer before we were married.”94Qtd by Sandra Y. Govan, Gwendolyn Bennett: Portrait of an Artist Lost. ProQuest Dissertations Publishing, 1980. pp. 83-84.

Imagining Shakespeare’s sister, Woolf concludes that she “was an unhappy woman, a woman at strife with herself. All the conditions of her life, all her own instincts, were hostile to the state of mind which is needed to set free whatever is in the brain.”95Virginia Woolf. A Room of One’s Own. Foreword by Mary Gordon. San Diego, New York, and London: Harcourt Brace & Company, 1981. pp. 50-51. Gwendolyn Bennett may have been closer to Shakespeare’s 16th century sister than the modern Mary Seton, Mary Beton, and Mary Carmichael Woolf evokes as her contemporaries. Those Mary’s (English women over 30) received the vote in 1918 and, by 1928, could vote at age 21. Black women will not earn the right to vote in the U.S. until 1965. It will be another 35 years before she is recognized as a person and citizen. How long until she is recognized as an artist?

Epilogue

Few, then or now, recognized young black women as sexual modernists, free lovers, radicals, and anarchists, or realized that the flapper was a pale imitation of the ghetto girl. They have been credited with nothing: they remain surplus women of no significance, girls deemed unfit for history and destined to be minor figures.96Saidiya Hartman. Wayward Lives, Beautiful Experiments: Intimate Histories of Social Upheaval. W. New York and London: W. Norton & Co., 2019. p. xv.

> Saidiya Hartman, Wayward Lives, Beautiful Experiments (2019)

In Wayward Lives, Beautiful Experiments Saidiya Hartman recovers the “intimate histories of riotous Black girls, troublesome women, and queer radicals” who in the first decades of the twentieth century struggled “to create autonomous and beautiful lives, to escape the new forms of servitude awaiting them, and to live as if they were free.”97Saidiya Hartman. Wayward Lives, Beautiful Experiments: Intimate Histories of Social Upheaval. W. New York and London: W. Norton & Co., 2019. pp. xviii-xiv. These women defied systems of white power, authority, and privilege that classified them merely as a problem, deeming them “unfit for history and destined to be minor figures.”98Saidiya Hartman. Wayward Lives, Beautiful Experiments: Intimate Histories of Social Upheaval. W. New York and London: W. Norton & Co., 2019. p. xv. Coming from an educated, middle-class background, Gwendolyn Bennett enjoyed advantages many of these women lacked. Yet she too seemed destined to be “a minor literary figure and graphic artist,” even by the scholars who worked so hard to restore her legacy.99Walter C. Daniel and Sandra Y. Govan. “Gwendolyn Bennett.” Afro-American Writers from the Harlem Renaissance to 1940, edited by Trudier Harris and Thadious M. Davis, Thomson Gale; Gale Cengage; 7Letras, 1987, pp. 3–10.

Yet if we look closely at Bennett’s life and surviving work, “a very unexpected story of the twentieth century emerges, one that offers an intimate chronicle of black radicalism, an aesthetical and riotous history.”100Saidiya Hartman. Wayward Lives, Beautiful Experiments: Intimate Histories of Social Upheaval. W. New York and London: W. Norton & Co., 2019. p. xv. In Bennett’s case, that history is the story of a Black woman who made bold experiments in life, art, and writing. Some of her work was published, some left unfinished, and much was lost or burned to ashes. “The wild idea that animates” this website is that Gwendolyn Bennett, like the young Black women whose lives Hartman chronicles, was a radical thinker, versatile artist, and creative writer “who tirelessly imagined other ways to live and never failed to consider how the world might be otherwise.”101Saidiya Hartman. Wayward Lives, Beautiful Experiments: Intimate Histories of Social Upheaval. W. New York and London: W. Norton & Co., 2019. p. xv.

Even without a studio of her own or a legacy of £500 per year, even in the face of persistent debts, disappointments, and obstacles, Gwendolyn Bennett never gave up on her dreams of artistic and romantic fulfillment. When broken illusions sapped her enthusiasm for painting, when she could no longer publish poems for fear of arrest for Communist sympathies, she channeled her creative energies into art advocacy and community building at the Harlem Community Arts Center, and later into teaching and uplifting young artists and writers at the School for Democracy and the George Washington Carver School. After her disappointing marriage to Dr. Alfred Jackson failed and her subsequent rocky romance with artist Norman Lewis nearly destroyed her self-respect, she found lasting happiness with white educator Richard Crosscup at a time when interracial marriage was socially taboo and downright illegal in 31 states. After working for Consumers Union for twenty years, Bennett retired and moved with Richard to Kutztown, Pennsylvania, where in 1970 they opened an antique shop, Buttonwood Hollow Antiques. They enjoyed another decade of romantic and professional partnership before he died in 1980; she died the following year.

When traditional paths to artistic success are closed to you, who is to say that to paint without a studio, write poetry without chance of publication, forge a loving partnership across racial lines, and design a home filled with carefully curated antiques, do not add up, in the sum of a life, to major creative achievements?

Works Cited

- Bennett, Gwendolyn. Gwendolyn Bennett Papers, Beinecke Rare Book and Manuscript Library, Yale University.

- Bennett, Gwendolyn, and Frank Horne. Gwendolyn Bennett Papers, 1916-1981. Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture, The New York Public Library.

- Bennett, Gwendolyn. Heroine of the Harlem Renaissance and beyond: Gwendolyn Bennett’s Selected Writings. Eds. Belinda Wheeler and Louis J. Parascandola. The Pennsylvania State University Press, 2018.

- Daniel, Walter C., and Sandra Y. Govan. “Gwendolyn Bennett.” Afro-American Writers from the Harlem Renaissance to 1940, edited by Trudier Harris and Thadious M. Davis, Thomson Gale; Gale Cengage; 7Letras, 1987, pp. 3–10.

- Du Bois, W. E. B. The Souls of Black Folk. Ed. by Henry Louis Gates Jr. and Terri Hume Oliver. New York and London: W. W. Norton & Co., 1999.

- Govan, Sandra Y. Gwendolyn Bennett: Portrait of an Artist Lost. ProQuest Dissertations Publishing, 1980.

- Hartman, Saidiya. Wayward Lives, Beautiful Experiments: Intimate Histories of Social Upheaval. W. New York and London: W. Norton & Co., 2019.

- Honey, Maureen. Aphrodite’s Daughters: Three Modernist Poets of the Harlem Renaissance. Rutgers University Press, 2016.

- Lorde, Audre. “Age, Race, Class, and Sex: Women Redefining Difference.” Sister Outsider. Crossing Press, 2007. pp. 114-123.

- Woolf, Virginia. A Room of One’s Own. Foreword by Mary Gordon. San Diego, New York, and London: Harcourt Brace & Company, 1981.

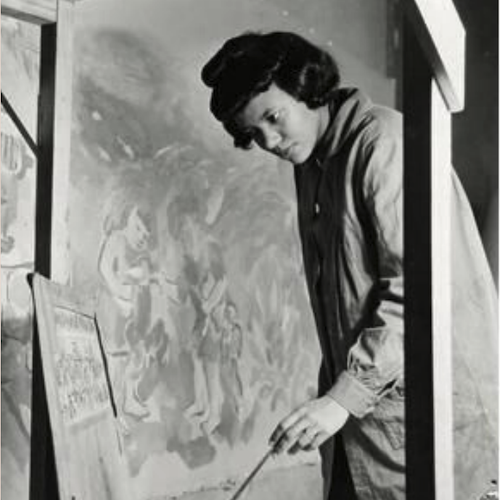

Featured Image

The photo that appears on the homepage as the featured image for this scene has been attributed to Bennett without citation, but Sandra Govan and I agree that it probably isn’t her. Although Bennett’s backward slanting handwriting suggests she was left-handed, her face was rounder than this woman’s, whose hairstyle appears to date from the 1950s, rather than the 1920s. The style of the painting also doesn’t resemble the few surviving images of Bennett’s oil paintings.