Social Media Influencer

Gwendolyn Bennett’s poems and illustrations appeared with impressive frequency in magazines of the 1920s, especially in Opportunity, where editor Charles Johnson was a supportive mentor to her. Her magazine publications demonstrate her responsiveness to the artistic currents and fashion trends of the time. In the contemporary social media landscape, originality may be less important than the ability to put a fresh spin on established meme, look, or move: TikTok videos, for example, proliferate with endless versions of the same dance routine. Like social media influencers today, Bennett picked and recombined emerging signals from across the arts in and blended them in her own fresh, enticing multimedia compositions. In her embrace of popular styles and fashions, she does not fit the mold of the avant-garde genius who shatters bourgeois conventions of taste and tradition. Nevertheless, she deserves recognition as an artist whose work synthesizes the moods of the era and documents a pivotal moment in American cultural history.

Bennett’s poetry is celebrated for its “visual sensibilities”—“as though she were painting with words” (Langley and Govan 9). In addition to its visual artistry, her poetry draws upon music, dance, and performance, emphasizing song, rhythm, and movement. Her poem “Heritage” (Opportunity, Dec. 1923, 371) taps into Africanist motifs that had recently become popular as a resource for restoring a sense of cultural lineage for the “New Negro,” whose historical ties had been ravaged by the violence of the transatlantic slave trade and further degraded by prohibitions against Black literacy and education. The poem comprises a series of unrhymed tercets, or three-line stanza, that call forth the sounds and images of ancient Africa that the speaker longs to see.1Bennett, “Heritage,” Heroine of the Harlem Renaissance and Beyond: Gwendolyn Bennett’s Selected Writings, ed. by Belinda Wheeler and Louis J. Parascandola, The Pennsylvania State University Press, 2018, p. 24. The first stanza sets the scene and the second inhabits it with young Black girls:

I want to see the slim palm-trees, Pulling at the clouds With little pointed fingers... I want to see lithe Negro girls, Etched against the sky While sunset lingers.

With the clouds seemingly drawn by hand, the poem emphasizes the artifice of the “etched” scene, representing Africa as an imagined space that stimulates the modern imagination, rather than an authentic, primitive place. In the final stanza, Bennett puts the idealized African scenes in sharp relief against the contingencies of the present day:

I want to feel the surging Of my sad people’s soul Hidden by a minstrel-smile.

The ironic revelation of the last line exposes how Primitivist performances may be misconstrued by white audiences who see the “minstrel-smile” but fail to detect more complex expressions of pain, desire, and aspiration. Bennett’s poem strikes a delicate balance between the desire to extricate “my sad people’s soul” from the legacies of slavery and white supremacy, and the urge to connect “lithe Negro girls” to an African heritage in order to affirm their beauty.

Her 1925 poem “Song” similarly features “A dancing girl with swaying hips” in a lyric that blends African American musical traditions into a modern medley.2First published in The New Negro: Voices of the Harlem Renaissance, ed. Alain Locke (New York: Boni and Liveright, 1925), p. 225; reprinted in Bennett, Heroine of the Harlem Renaissance, pp. 26-7.

I am weaving a song of waters, Shaken from firm, brown limbs, Or heads thrown back in irreverent mirth. My song has the lush sweetness Of moist, dark lips Where hymns keep company With old forgotten banjo songs.

Bennett’s “Song” incorporates the sounds and rhythms of sorrow songs (“the cry of a soul”), folk tunes and work songs (“A-shoutin’, in de ole camp-meetin’ place”), lullabies (“mothers hold brown babes”), and jazz (“Singin’ slow, sobbin’ low”), concluding on a jazzy, upbeat note:

Sing a little faster, Sing a little faster, Sing!

In the figure of the female African dancer, the repetition of lines, and exhortation to “Sing!” you may detect echoes of Langston Hughes’s 1922 poem “Danse Africaine”:

The low beating of the tom-toms,

The slow beating of the tom-toms,

Low . . . slow

Slow . . . low —

Stirs your blood.

Dance!

Bennett definitely learned from the example of her good friend Langston Hughes. But although her poetry is sometimes belittled as imitative, it is better understood as responsive and synergetic. She was like a sensitive antenna, picking emerging signals from across the arts and recombining them in her own multimedia work.

<>

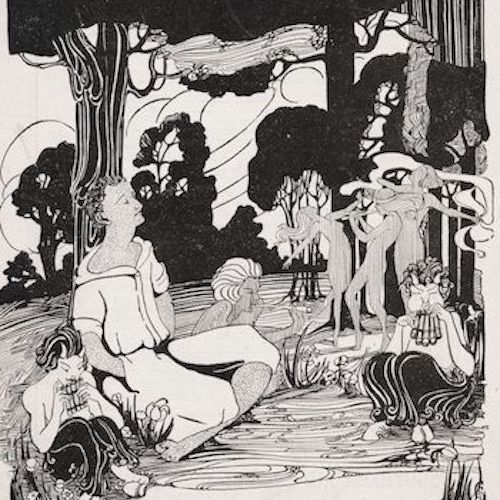

Just as Bennett’s poems sample sounds and images from the poetry of Hughes, Cullen, and other writers and draw upon various African American musical traditions, her 1920s cover illustrations for the Crisis and Opportunity recombine trends in the visual arts.

This illustration adopts Art Nouveau aesthetics, depicting fauns and female fairy dancers in a woodland setting, using curved, organic lines and an Aubrey Beardsley-esque embrace of decadent indulgence in sensory pleasure. Its central figures are dark-skinned, including a seated man, a pipe player, and three naked female dancers. The main figure, seated with eyes closed and hands in pockets, is patently not at work, thereby defying the masculine, American, middle class work ethic in favor of the leisurely pleasures of listening to music in a pastoral setting. By adopting French and British artistic styles in a deliberately racialized scene, Bennett positions brown-skinned figures within sophisticated European aesthetics. She both helps spread these aesthetics to African American readers and claims a place for them within contemporary artistic developments. Combining influences of Art Nouveau and European decadence and embracing the “art for art’s sake” ethos, the illustration issues a form of subtle resistance to African American uplift ideology, asserting that Black people have just as much right to leisure, play, beauty, and sensual pleasure.

Two years later, while living and studying art in Paris, Bennett created a cover illustration for Opportunity that combines Art Deco aesthetics with the style and rhythm of Josephine Baker in her own expression of Black Deco.

But that’s a story for another scene. Here, our concern is with her work as a social media influencer

<>

Nowhere is Bennett’s role as social influencer more evident than in her monthly column, “The Ebony Flute,” which ran in Opportunity from 1926 to 1928. The column, which she described as “literary chit-chat and artistic what-not,” tracks developments in Black arts with a mix of friendly gossip, rhapsodic appreciation, and sharp-witted critique. The column enacts a form of call and response—a call to community engagement and a response to developments in the arts.

Elizabeth McHenry links “The Ebony Flute” to African American literary salons and societies, such as Georgia Douglas Johnson’s “Saturday Nighters”—“an important institution where writers and intellectuals gathered regularly to exchange ideas about literature and to talk about writing.”3McHenry, Forgotten Readers: Recovering the Lost History of African American Literary Societies. Duke University Press, 2002, p. 291. “The Ebony Flute” not only provided news about these literary societies, but also served many of the same social functions. The column provided encouragement and community to aspiring artists and writers, illustrating “that the literary renaissance so intensely experienced in New York City’s Harlem was indeed sweeping through black communities across the nation” and “raising her readers’ awareness of the indisputable fact that collective reading and writing groups were being formed everywhere”4McHenry, Forgotten Readers, pp. 292-3. But Bennett didn’t confine her attention to literary developments: she was equally interested in celebrating the visual, musical, and performing arts.

Bennett’s column is conversational in form, stitching together quotations and mentions via ellipses that resemble tiny stitches in a patchwork quilt or dots in a batik design. Think of the various items as tweets on Twitter, which prompt likes, replies, and further conversations. Early on, she reports an exchange with poet Clarissa Scott [Delaney], in which “the question arose as to what was the most beautiful line of poetry written by a Negro” (August 1926). The query generates a flurry of responses: Aaron Douglas nominated lines from Jean Toomer’s “Georgia Dusk,” and Robert Frost submits lines from Helene Johnson’s “The Road” (Sept 1926):

Ah, little road, brown as my race is brown, Your trodden beauty like our trodden pride, Dust of the dust, they must not bruise you down.

Frost’s contribution indicates not only that he read Opportunity magazine—and Bennett’s column—with great interest, but also that the conversation she staged built an artistic and literary network that transcended racial and geographical divides.

Bennett’s column also fostered intergenerational connections within the Black arts community. In October 1926, her third column, Bennett mentions the receipt of a “very charming” letter from Georgia Douglas Johnson, who declares that she “likes the column,” and another from William Stanley Braithwaite, who says how much he looks “forward to each month as a sort of personal chat with you about books and things.” Braithwaite describes the column not simply as “chat” or light conversation, but “personal chat with you” [emphasis added], suggesting a more intimate dialogue. Bennett creates the impression that, when we read “The Ebony Flute,” we are having a personal chat with her. She’s curious, observant, enthusiastic, and occasionally witty and wry—a delightful conversationalist.

As much as she creates an impression of spontaneity, Bennett crafts her column as an orchestrated conversation—a conversation as performance. Her review of Claude McKay’s Home to Harlem uses the conceit of a symphony to describe the way he writes about Harlem, incorporating various voices and themes into the composition. The “Ebony Flute” column is less a symphony than a jazz composition, with short riffs, repeated themes, and an improvisational, meandering style. Rather than adopting the objective tone of the art critic, she makes commentary about the arts personal and social, though no less discerning or selective.

Like so many social media influencers today, whose glamorous online personas may gloss over their personal struggles, the poise and optimism Bennett conveys in the “Ebony Flute” belie the turmoil in her personal life. Bennett began writing “The Ebony Flute” in August 1926, shortly after her return from Paris to New York, during a time of great transition and upheaval in her personal life. Her plans for a “homecoming exhibition” of her art were derailed by her father’s sudden death in a subway accident. Still reeling from the trauma, she had to leave her beloved Harlem community to take up residency in D.C. and teach art at Howard University. But that, too, is a story for another scene.